If Words Are "Just Words" Why Do They Burn: From Conversion Therapy to LGBTQ+ Inclusive Healthcare

Ostrowski (2016)

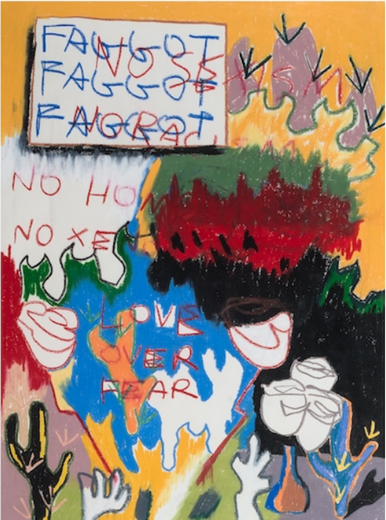

If Words Are “Just Words” Why do they Burn by Stephen Nestor Ostrowski is a work that overlays insults against the LGBT+ community with affirmations of acceptance such as “love over fear” (Ostrowski, 2016). Within this piece, the artist may be reflecting on their own experience of surviving conversion therapy and their subsequent healing from this trauma (Montague, 2023).

Research:

In 2018, 19% of those who reported experiencing conversion therapy in the UK had it conducted by healthcare professionals (UK Government Equalities Office, 2018) despite the fact that all of the NHS bodies in the UK have signed the memorandum of understanding of conversion therapy in the UK in 2017 (Memorandum of understanding on conversion therapy in the UK, 2022), recognizing it as an unethical, potentially harmful, non-evidence-based practice. This artwork is included in a Wellcome collection article titled “the indelible harm caused by conversion therapy,” which uses a series of Ostrowski’s work to chart the history of conversion therapy in the UK medical establishment (Montague, 2023). I see conversion therapy as an extreme example of the wider stigmatization of the LGBTQ+ community by the medical establishment; it is considered torture by the United Nations (United Nations, 2020).

The assumption of cis heterosexuality, something I have personally experienced in a medical setting, is a micro-aggression due to its erasure of identity, engendering a sense of shame at my otherness from what is considered normal by society. This happening repeatedly causes many to internalize shame, which may partly explain why people in the LGBT+ community have an increased rate of mental health conditions (UK Government Equalities Office, 2018). This piece resonated with me because it reminds me of my own struggle with internalized homophobia and challenged me to consider how I could help patients in marginalized groups heal from being subjected to stigma as it is likely to impact their health.

Why words burn?

What struck me most about this artwork is the vividness of the colors used. The intensity of them perhaps emulates the artist's suffering as a result of having undergone conversion therapy. Similarly, the boldness of the artwork commands the observer to take notice of its messages. As a member of the public, I am outraged that conversion therapy is still purported to have been offered to 7% of the LGBTQ+ community (UK Government Equalities Office, 2018). The contrast between the slur “faggot” and the slogan “love over fear” could represent a catharsis releasing the conflict between homophobic ideologies they have been indoctrinated in and their attempts as an adult to diminish these during the healing process. I find challenging the artist’s decision to include the term “faggot” given its connotation of violent hate crime against the LGBTQ+ community. However, it could be said that in doing so, Ostrowski has reclaimed this term, removing the power of oppressors through taking language from them. The work’s title questions the idiom “words are just words” by describing them as “burning.” This comparison of the harm that slurs and microaggressions can cause to a scorching pain demonstrates the suffering that can be caused by language that others those from marginalized communities.

Reflection:

As a medical student, one of the most significant issues this artwork has prompted me to reflect on is how vital it is that healthcare professionals operate under a strong ethical framework to prevent them from carrying out so-called treatments detrimental to patients’ well-being. There is no evidence that it is possible to change someone’s sexual orientation and that trying to do so will likely result in psychological harm. Considering the ethical principle of justice, it is vital that the NHS works towards increasing LGBTQ+ access to healthcare. Unfortunately, there are woefully long waiting lists to access gender identity services on the NHS in almost every nation in Great Britain. It could be said it represents an inequity, perhaps due to a lack of investment into these services to reduce the waiting times, despite them providing potentially life-saving treatment that can greatly improve the mental health of trans and non-binary people (Ellis, Bailey and McNeil, 2015).

It could be argued that the lack of access to gender-affirming healthcare constitutes a form of conversion therapy, as it may force some to continue to live as a gender they do not identify with due to their lack of safety living as their preferred gender until they can change their appearance in a way that allows them to “pass” as cisgender. This demonstrates the importance of building a healthcare service that centres the concerns of all groups, including transgender and non-binary people, especially as increasing equality for LGBTQ+ people is linked with increasing their health (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2012), thus could provide a financial saving for healthcare services. The title of the artwork caused me to consider how I as a future healthcare professional, could be involved in reducing the harm of microaggressions to improve the rapport I build with patients. For example, using language that includes all genders to avoid misgendering someone. Additionally, I would ask patients how they would prefer to be addressed as this can help build rapport as it demonstrates that you, as a healthcare professional, respect their identity. Overall my appreciation for the value of arts within medicine has increased as looking at art gives me a deeper insight into the experiences of others, increasing my empathy for those with similar experiences.

Additionally, this artwork allowed me to connect with my community as I became more aware of the severity of oppression many LGBTQ+ people sadly endure. This intensifies my desire to participate in activism to improve the lives of LGBTQ+ people worldwide. Learning about the history of conversion therapy in the UK gave me a greater appreciation of the context of the current campaign to ban conversion therapy in the UK for all members of the LGBTQ+ community. I learned that a large proportion of conversion therapy in the UK is suffered by transgender people furthering my understanding of the need for societal change that increases the safety of this marginalized group (UK Government Equalities Office, 2018). Personally, this piece challenged me to consider whether I have truly rid myself of the homophobic and transphobic ideologies instilled in me from a young age. I have reflected that despite coming out, I still to some extent, feel shame about my sexuality and gender identity. I am using journaling to further assist myself in identifying and challenging these negative thoughts to improve my well-being.

Conclusion:

Initially, I felt this artwork serves as a painful reminder that conversion therapy, albeit rarely, is still practiced in healthcare settings in the UK despite these measures and the harm the LGBTQ+ community has suffered at the hands of healthcare professionals who should be working to improve their wellbeing. However, my perception of this piece has changed in that it, whilst serving as a reminder of mostly historical abuses, it simultaneously provides a prompt for reflection on the efforts of healthcare professionals in recent decades to improve the safety of LGBTQ+ patients, for example by signing the memorandum of understanding of conversion therapy in 2017 (Memorandum of understanding on conversion therapy in the UK, 2022). This and other measures to promote acceptance are likely to have increased the trust between the LGBTQ+ community and healthcare professionals.

Written by Cerys Chitty | Medical Student

References:

Ellis, S.J., Bailey, L. and McNeil, J. (2015). Trans People’s Experiences of Mental Health and Gender Identity Services: A UK Study. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 19(1), pp.4–20. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/19359705.2014.960990

Hatzenbuehler, M.L., O’Cleirigh, C., Grasso, C., Mayer, K., Safren, S. and Bradford, J. (2012). Effect of Same-Sex Marriage Laws on Health Care Use and Expenditures in Sexual Minority Men: A Quasi-Natural Experiment. American Journal of Public Health, 102(2), pp.285–291. doi:https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/full/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300382

Memorandum of understanding on conversion therapy in the UK. (2022). https://www.bacp.co.uk/events-and-resources/ethics-and-standards/mou/

Montague, J. (2023). The indelible harm caused by conversion therapy. [online] Wellcome Collection. Available at: https://wellcomecollection.org/articles/Y2lGphEAAKLNeMjY [Accessed 10 Mar. 2023].

Ostrowski, S. (2016). If words are ‘just words’ why do they burn?.

UK Government Equalities Office (2018). National LGBT Survey. pp.83–95.United Nations (2020). Independent Expert on protection against violence and discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity [online] https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Issues/SexualOrientation/ConversionTherapyReport.pdf Available at: Independent Expert on protection against violence and discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity [Accessed 25 Mar. 2023].