Having returned from working in Calais, where I distributed material aid to displaced people, it felt apt to decompress by attending “A Walk Through the Tate Modern on the Theme of Migration”. Uniquely to this latest stint in Calais, I was a medical student. I was struck by how this pivoted my outlook: my capacity to provide help was no different, nor were the encounters I had. I believe my interpretation of Rechmaoui’s “Monument for the Living” encapsulates this change, which I hope will be formative in my future career.

Having volunteered in Lebanon 2 years ago, I was immediately struck by the resemblance of the sculpture to buildings in Lebanon—before realising that it is indeed a replicate of the “Burj al Murr” tower in Beirut, whose construction began in 1974 and halted the following year after the onset of the Civil War (Tamimova, 2022).

“Monument for the Living” by Marwan Rechmaoui. (Tate Modern, 2023).

For me, Lebanon, the country with the highest number of refugees per capita in the world (Janmyr, 2017), is inextricably linked to displaced communities. The rationale for the sculpture’s inclusion in this collection, namely that “Buildings are often at the heart of refugees’ troubles.” (Tate Modern, 2023) made me reflect on the often inaccessible healthcare support for displaced people (Lebano et al., 2020). This is because of the established psychological benefits of maintaining connections to homelives left behind (betoken by the abandoned sculpture) (Griswold et al., 2021), yet the difficult practicality of this and evident multifaceted mental health implications (Woodward et al., 2022).

However, while my outlook as a member of the public remains appalled by the challenges people face, as someone training to work within the constraints of the NHS my outlook has pivoted downstream to healthcare inaccessibility for marginalised groups, particularly psychological support, especially given that in Calais, displaced people are present solely to reach the UK (Lebano et al., 2020).

The Sculpture: Monument for the Living

Interestingly, a “monument” denotes something fixed and unchanging in time, contrary to what it means to be “living”. The sculpture is stark both in colour and brutalist design, engendering bleak and despondent feelings and echoing the ongoing financial crisis responsible for the decrepit built world in Lebanon. This is further emphasised by the meaning of “Burj al Murr”: the Tower of Bitterness (Tate Modern, 2023). Indeed, “bitterness” conveys outstanding discontent, and so it feels fitting that this sculpture is a second replicate following the destruction of the first: broader circumstances do not change the condition of the building or sculpture, nor the experience of the living.

The Sculpture and the Theme of Migration: Monument for the Moving

Certain features of the sculpture are particularly potent: despite all the windows, there is no door. Movement is thus restricted. Yet, as spectators on the outside, we are permitted to freely move around the sculpture, conjuring thoughts about systemic differences in migration.

In fact, I was reminded of the moving by the sculpture, not the living. Considering the tower as representing a lived situation, I thought more about systemic differences upon discovering that the Burj al Murr building is now structurally unsound (Tamimova, 2022). Despite this systemic fault, force cannot be used to deconstruct the tower as it is too intimately placed in surrounding neighbourhoods (Tamimova, 2022). Yet, I have personally seen arguably ineffective border policies be forcefully enacted despite the damage to people on the move, i.e., the moving.

Monument for the Moving: Access to Healthcare

The scope for the inanimate building to acquire new meaning and yield different interpretations led to its inclusion in the collection, which is what made me consider the moving in relation to healthcare.

Some have likened the sculpture to the skeleton of the Grenfell fire in the UK (Pilcher, 2023) and I overheard others in the exhibition associate the Beirut blast. Other interpretations of the sculpture include that of El Hachem who asserts that "Burj El Murr is the legacy of the war" (Hachem, 2019) as well as that of the Tate curator who reflects that “Buildings are often at the heart of refugees’ troubles.” and of displaced people “breathing new life” into buildings in the UK (Tate Modern, 2023). I find the latter interpretation the most thought-provoking. Rather than imagery of refugees inhabiting buildings, I am reminded of the number of vacant buildings in Lebanon and the tent settlements I worked in that Syrian people have lived in for 11 years since coming to Lebanon (Montero Kuscevic and Radmard, 2020)—and therefore, of their lack of connection to any conventional home and the associated mental health challenges, as aforementioned (Griswold et al., 2021).

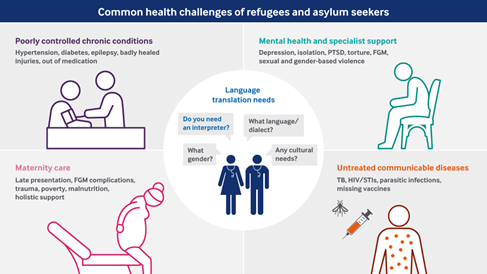

Both internally and externally displaced adults and children often have complex presentations associated with healthcare accessibility barriers (Lebano et al., 2020), as outlined below.

“Common health challenges of refugees and asylum seekers”. (British Medical Association, 2022)

A key contextual factor in UK healthcare accessibility is the government’s policy to create a hostile environment (Uthayakumar-Cumarasamy, 2020). This manifests in reluctance amongst people to access healthcare for fear of patient confidentiality breaches affecting asylum claims (British Medical Association, 2022). Moreover, of those who do come forward and are eligible, many are wrongly refused access to even primary care (British Medical Association, 2022). Beyond this, many accounts of those granted access find the NHS difficult to navigate (Kang, Farrington and Tomkow, 2019). I thought the following hurdles predominated the literature: interpretation is frequently denied and people are incorrectly charged for secondary care due to being mistaken as “foreign visitors” (Kang, Farrington and Tomkow, 2019).

To anticipate contrary opinions, it is noteworthy that there is no evidence of the disproportionate use of NHS resources by migrants and asylum seekers (Refugee Council, 2021).

Appreciating alternative patient lenses is important because I believe as a healthcare worker, to uphold ethical and professional principles such as safeguarding vulnerable patients (Snape and Elliott, 2011), endeavouring to facilitate access to resources by learning about biases in the treatment of marginalised groups is vital (Hui et al., 2020). For instance, this reflection has already led to my awareness of other marginalised groups, namely those with mental health problems (Cheraghi-Sohi et al., 2020). Given the presence of several measurable marginalised groups and the demonstrable repercussions from healthcare inaccessibility outlined, I believe more attention ought to be dedicated to addressing these disparities professionally, but also as conscientious, ethical members of society.

Conclusion

Most striking to me is the development in my response to the sculpture, which has been made crudely evident in the process of writing this: the depth of my interpretation has shown me that perception is not in the eye of the receiver but rather, in the mind’s eye. The tangibility of this is demonstrated by the various aforementioned interpretations of Rechmaoui’s sculpture which are forged by personal experience, highlighting the transformative trajectory of the learnings uncovered in this written piece. Hence, while my impression as a lay member of the public is mostly shaped by “small migrant boat crisis” news headlines, my perception is elaborated by my role as a medical student.

As mentioned in the very first sentence, I went to the exhibition primarily to decompress—to cope with emotional work and change responsibly. Thus, it feels full circle to the matter at hand to reflect on this again in the last sentence: both physical and mental health must be proactively nurtured, both broadly within the healthcare system and personally as a professional with personal responsibility for one’s own actions and health in complex and uncertain situations (Snape and Elliott, 2011).

Written by Elizabeth Tasker, Medical Student.

References

- Cheraghi-Sohi, S. et al. (2020) ‘Patient safety in marginalised groups: A narrative scoping review’, International Journal for Equity in Health. International Journal for Equity in Health, 19(1) https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32050976/.

- Griswold, K. S. et al. (2021) ‘“I just need to be with my family”: resettlement experiences of asylum seeker and refugee survivors of torture’, Globalization and Health. Globalization and Health, 17(1), pp. 1–7. https://globalizationandhealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12992-021-00681-9.

- Hachem, E. (2019) 'The man who turned Beirut's infamous Burj El Murr into a fairy tale'. Available at: https://www.thenationalnews.com/arts-culture/film/the-man-who-turned-beirut-s-infamous-burj-el-murr-into-a-fairy-tale-1.872423 (Accessed: 22 January 2023).

- Hui, A. et al. (2020) ‘Exploring the impacts of organisational structure, policy and practice on the health inequalities of marginalised communities: Illustrative cases from the UK healthcare system’, Health Policy. Elsevier Ireland Ltd, 124(3), pp. 298–302. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0168851020300063.

- Janmyr, M. (2017) ‘No country of asylum: “Legitimizing” Lebanon’s rejection of the 1951 refugee convention’, International Journal of Refugee Law, 29(3), pp. 438–465.https://academic.oup.com/ijrl/article/29/3/438/4345649

- Kang, C., Farrington, R. and Tomkow, L. (2019) ‘refusa’, British Journal of General Practice, 69(685), pp. E537–E545. https://bjgp.org/content/69/685/e537

- Lebano, A. et al. (2020) ‘Migrants’ and refugees’ health status and healthcare in Europe: A scoping literature review’, BMC Public Health. BMC Public Health, 20(1). https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-020-08749-8

- Montero Kuscevic, C. M. and Radmard, H. (2020) ‘Syrian refugees in Lebanon: a spatial study’, Applied Economics Letters. Routledge, 27(5), pp. 417–421. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13504851.2019.1623862

- Pilcher, A. (2023) 'Why I Love Marwan Rechmaoui's Monument for the Living'. Available at: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/rechmaoui-monument-for-the-living-t13193/marwan-rechmaouis-monument-living (Accessed: 23 January 2023).

- Refugee Council (2021) 'Healthcare for refugees: Where are the gaps and how do we help?'. Available at: https://www.refugeecouncil.org.uk/latest/news/healthcare-for-refugees-where-are-the-gaps-and-how-do-we-help/ (Accessed: 23 January 2023).

- Snape, J. and Elliott, B. (2011) ‘Good medical practice.’, BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 342. https://www.bmj.com/content/342/bmj.d3949

- Tate Modern (2023) 'A Walk Though Tate Modern On the Theme of Migration'. Available at: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/walk-through-tate-modern-on-theme-migration (Accessed: 23 January 2023).

- Tate Modern (2023) 'Marwan Rechmaoui: Monument for the Living'. Available at: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/rechmaoui-monument-for-the-living-t13193 (Accessed: 21 January 2023).

- Tamimova, M. (2022) ‘Concrete sectarianism: Revisiting the Lebanese civil war through Beirut’s built environment’, Ethnography, 0(0), pp. 1–19. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/14661381211067451

- Uthayakumar-Cumarasamy, A. (2020) ‘The “hostile environment” and the weaponization of the UK health system’, Medicine, Conflict and Survival. Routledge, 36(2), pp. 132–136. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32419480/

- Woodward, A. et al. (2022) ‘Scalability of a task-sharing psychological intervention for refugees: A qualitative study in the Netherlands’, SSM - Mental Health. The Authors, 2(August), p. 100171. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2666560322001116